It is a victory, albeit one that came late and resulted from a battle that shouldn’t have had to be fought in the first place.

On Thursday, FIBA, basketball’s international governing body, voted unanimously to overturn Article 4.4.2 in its official rulebook — the rule that prohibited players from wearing headgear on the court that included hijab headscarves, turbans and yarmulkes.

The rule drew widespread criticism in recent years because, whether intended or not, it prevented many Muslim women, Sikh men and Jewish men from being able to play the sport in FIBA-sanctioned competition while still following certain religious customs.

In 2014, FIBA implemented a two-year “testing phase” where they would allow the previously prohibited headgear in certain games and tournaments to review if it was actually unsafe of otherwise worth being prohibited. While some hoped a decision would be reached before the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the final vote didn’t take place until this week.

The official modified rule states, according to the Associated Press, that allowing headgear must be “black, white or the same dominant color as the uniform for all players. It cannot cover any part of the face, have no opening or closing elements around the face and/or neck, and have no parts that extrude from its surface.”

The decision comes too late for hundreds or maybe even thousands of athletes who have been negatively impacted by the rule. It’s hard to quantify exactly how many because you have to consider, for example, the number of young Muslim women, Sikh men and Jewish men who perhaps never even took up basketball because they never saw people who looked like them playing on TV.

But then there are real, tangible cases like the one of Bilqis Abdul-Qaadir.

A high school basketball phenom who owns the Massachusetts state scoring record and went on to become a star in college, Abdul-Qaadir finished her senior season at Indiana State University in 2014. At the time, she had the talent and ability to play professionally, but because she chooses to represent her Islamic faith by wearing a hijab headscarf on the court — which was allowed in high school and in college — most FIBA-sanctioned pro teams wouldn’t sign her, because to play Abdul-Qaadir or any other woman wearing a hijab headscarf could lead to the team having to forfeit the game.

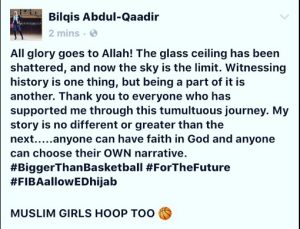

Abdul-Qaadir hasn’t played a pro game. Having now spent three years away from playing competitively, she may have lost her opportunity to fulfill a dream. But she has been at the forefront of the fight for FIBA to allow athletes like her to not have to choose between religion and sports. Shortly after the FIBA decision was announced, Abdul-Qaadir posted this on social media: