Fasting from both food and fluid all day, every day, for an entire month, puts the body under stress. And for many Muslims, that’s the point: the month of Ramadan is for spiritual reflection and devotion, self-discipline, and charity — not for doing what feels good or comes easy. It’s meant to be challenging.

Fasting from both food and fluid all day, every day, for an entire month, puts the body under stress. And for many Muslims, that’s the point: the month of Ramadan is for spiritual reflection and devotion, self-discipline, and charity — not for doing what feels good or comes easy. It’s meant to be challenging.

And it’s almost certainly going to affect your workouts, no matter how popular intermittent fasting has become in the fitness industry.

It’s Not Really Intermittent Fasting

Clearly you’re fasting intermittently, but capital I.F. Intermittent Fasting is an approach to eating that has become popular in recent years as a means for, among other things, controlling caloric intake and optimizing hormones. In fitness circles, it usually means restricting your feeding windows to a few hours per day, or fasting for 24 hours once or twice per week.

But there are a few important differences between the way Intermittent Fasting is popularly employed by internet fitness gurus and the way it’s traditionally undertaken during Ramadan.

“Training fasted is not always as awesome as it’s cracked up to be, especially because most people who talk about it on the internet aren’t doing a liquid fast,” says Brian St. Pierre, CSCS, the Director of Performance Nutrition at Precision Nutrition. “They’re maintaining hydration, they’re sipping on BCAAs while they train, they drink coffee beforehand. And they’re often just fasting during their sleep and then extending their morning fast a little bit, whereas during Ramadan you’re fasting during the majority of your waking hours. So it’s a little bit of a different animal in that regard.”

That doesn’t mean that it’s impossible to have a productive workout during a Ramadan fast, nor does it mean there’s no evidence that fasted training could have some benefits.

But truly fasted training, after hours of no fluid intake, performed every day — often during some of the hottest months of the year? There are several studies showing that athletic performance is likely to take a hit, at least for most people.

But you might be able to time your workouts to your advantage.

When Should I Exercise During Ramadan?

When Should I Exercise During Ramadan?

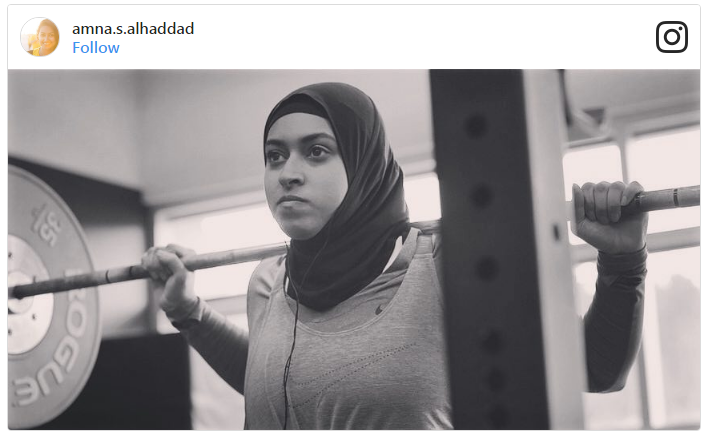

“The biggest mistakes I see Muslim lifters make is that they simply don’t train at all because they think they are going to lose muscle or they think they’re going to be too tired,” says Kulsoom Abdullah, a Pakistani-American weightlifter who was the first woman to compete completely covered in the International Weightlifting Federation. “They forget that we need time to adapt to the fast, so our first day of training could be less than ideal. Don’t get mad, sad, or disappointed. It is going to be OK. You are going to adapt, you will do amazing, and be happy with what you thought you couldn’t do because of fasting. It is very mental.”

In a perfect world, you would train an hour or two after consuming plenty of fluid and a small meal of protein, carbs, and a little healthy fat. During the month of Ramadan, that leaves a window either after a small iftar (the “break fast” consumed at sunset) or, if you’re extra ambitious, early in the morning after suhoor (the pre-dawn meal).

It’s important to note that we don’t live in a perfect world. Making time to work out after suhoor could mean losing out on precious sleep (and hampering your recovery), and while training after a small iftar is probably the most doable for the general population, many people would rather not sacrifice a lengthy, relaxing iftar with their loved ones.

It’s important to note that we don’t live in a perfect world. Making time to work out after suhoor could mean losing out on precious sleep (and hampering your recovery), and while training after a small iftar is probably the most doable for the general population, many people would rather not sacrifice a lengthy, relaxing iftar with their loved ones.

“That’s where you have to weigh competing demands,” says St. Pierre. “If (a long, communal iftar) is really important to you and to a lot of people it is — it would be to me, too — then train fasted and you just work around it. It’s just one month out of the year. You’re still going to be training hard before Ramadan and training hard after, which is why I really try to emphasize to clients to aim for maintenance. If we can make gains, that’s just gravy. But for most people the goal right now is to maintain strength and muscle mass.”

How Should I Exercise During Ramadan?

How Should I Exercise During Ramadan?

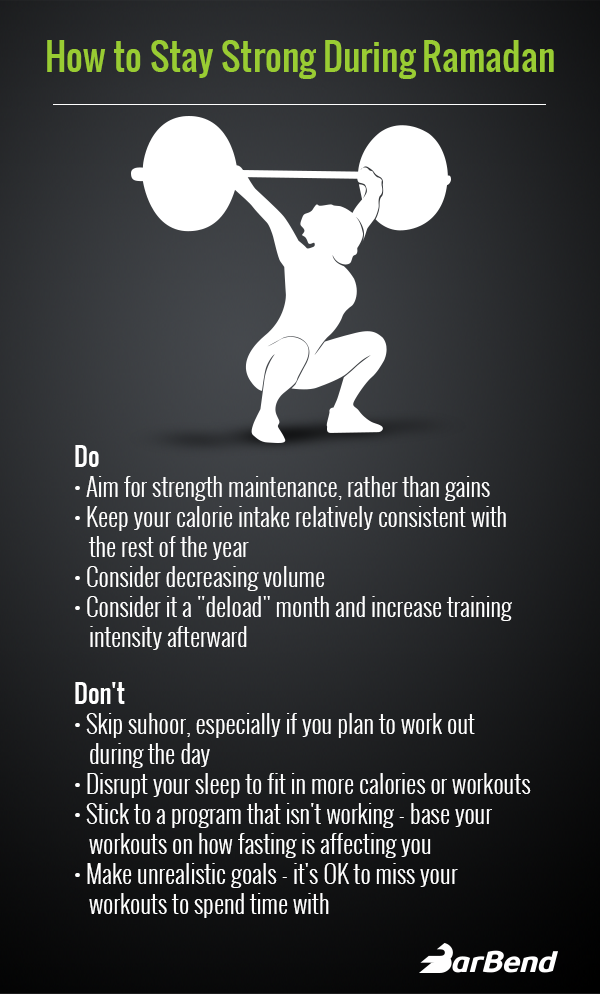

The general recommendation (remember, we’re only talking in generalizations, here) is to decrease volume and intensity during the first week of Ramadan as your body gets accustomed to the fasting.

“Whether you skip workouts for the first week or not is very individualized,” says Craig Weller, Precision Nutrition’s Exercise Systems and High-Risk Occupations Program Director. “Some people will be fine, others will need to ease in. Maybe you’re extra tired or more dehydrated than you’re comfortable with. Maybe you lose some muscle or don’t recover as well, but it’s unlikely that you’ll encounter anything worse than short-term discomfort and inconvenience. It’s not the best time to compete at a high level, but otherwise it’ll just be a speed bump and one more stressor to grow accustomed to.”

The most important thing to note here is that not everybody reacts the same. That’s why it’s a good idea to decrease volume and see how your lifts respond to the stress of fasting.

The most important thing to note here is that not everybody reacts the same. That’s why it’s a good idea to decrease volume and see how your lifts respond to the stress of fasting.

“It takes me a few days to get adapted to the fast, and I do less reps and shorter workouts,” says Abdullah. “With less reps, I sweat less and don’t feel as tired. These days are long days, and hot, so I have to be mindful about that. Electrolytes are important. The weight I play by ear. I push myself, just not enough to completely knock me out.”

“In my experience, I’d say most do best with a lower volume and some also need to lower intensity in terms of weights they use,” says St. Pierre. “I’ve seen some folks able to decrease at first and within a few weeks they’ve ramped up to their normal volume, but they’re not the norm. I’d say most people fall on a bell curve: a few will end up at their normal volume, most will end up at sixty to eighty percent of their regular volume, and some need to decrease both volume and intensity.”

After a week or two, you might find you can lift at your usual weight, but St. Pierre advises that most people will do best by decreasing their volume for the month as they aim for maintenance. For that reason, it’s a good idea to slightly reduce overall calorie intake to match the decrease in volume. (And yes, it’s a good idea to keep monitoring your calorie intake if you want your best shot at preserving muscle and strength.)

Can I Do Olympic Lifting During Ramadan?

Can I Do Olympic Lifting During Ramadan?

As far as programming goes, you may find that, depending on when you’re able to work out, it’s a little harder to perform extremely technical movements that require a lot of focus and precision, like the snatch. If that’s you, there are other ways to do power work that are less technique intensive.

“I might or might not do many Olympic lifts for the first few days, as for me, I notice the explosive movements are a bit more challenging at first,” says Abdullah. “Slow lifts I adapt to faster, like pulls, squats, an so on.”

“You can do box jumps, you can do med ball work, there are other ways to train power that are lower risk,” says St. Pierre. “Of course, often times, recommendations like that are just being cautious. But if you plan on lifting for the rest of your life, it’s just one month. There’s no sense in doing extreme things that could put you at increased risk of injury when really, it’s a very temporary thing. Why not take a break from Olympic weightlifting for that month and try a few other ways to work on power development that are low risk?”

Weller feels that in general, Ramadan can be a good time to focus on sub-maximal aerobic work and maybe some alactic power work so that, in his words, there’s less demand on glucose availability and you can take advantage of the lipolytic state that fasting will bias you toward.

Weller feels that in general, Ramadan can be a good time to focus on sub-maximal aerobic work and maybe some alactic power work so that, in his words, there’s less demand on glucose availability and you can take advantage of the lipolytic state that fasting will bias you toward.

“That means less anaerobic work and high-rep sets and more sustained work with a heart rate between about 130 to 150 beats per minute and bursts of strength that are no more than about ten seconds in duration, or maybe one to three reps,” he says. “No more than five.”

Again, this all depends on you. Don’t just follow advice you read on the internet, see how you’re responding.

Final Words

They’re clearly not the exact same thing, but St. Pierre drew a comparison between Ramadan and the month between Thanksgiving and Christmas: most of his clients usually aren’t spending that month focused on gaining strength, they’re focused on family, community, and spirituality. There’s no harm in putting strength training on the back burner for the month, and this way clients will attack their workouts with renewed vigor after it has come to an end.

We’re not about to tell anybody how to experience Ramadan. But we’re always happy to take the opportunity to remind you to treat yourself with kindness and to allow yourself to step back from training if you want to spend some time focused on other areas of your life.

The weights room will always be there. And while you can train during Ramadan, there’s nothing wrong with taking a break to turn inward.

Ramadan Mubarak.

By: Nick English

Featured image via @amna.s.alhaddad on Instagram.

For updates regularly visit: Allsportspk